La avenida de la Constitución de Sevilla es una amplia vía urbana de trazado

moderno y recto que une, a lo largo de 600 metros, la Puerta de Jerez con el edificio del Ayuntamiento en la plaza Nueva.

Situada en el distrito Casco

Antiguo, delimita en su trayecto los barrios del Arenal, al Oeste —desde la plaza Nueva

hasta la calle Adolfo

Rodríguez Jurado—, del de Santa Cruz, al Sur y

Este; perteneciendo al Arenal los números pares hasta el 36 inclusive, siendo

el resto parte de Santa Cruz. Además, marca el límite Sur del barrio de

la Alfalfa, en el cual se inscribe el

edificio del consistorio.

Arranca en su extremo Norte, más

próximo al Ayuntamiento, en la confluencia de las plazas Nueva y de San Franciscocon la calle

Fernández y González (del Arenal). A su lado par convergen, en

dirección Sur, las calles García de Vinuesa, Federico

Sánchez Bedoya, pasaje de los Seises y Almirantazgo, del barrio

del Arenal, y del barrio de Santa Cruz las calles Adolfo Rodríguez Jurado

y Maese Rodrigo.

Mientras que por el lado de los

impares lo hacen, hasta la puerta de Jerez, las calles Felipe Pérez, Alemanes, Fray Ceferino González, Santo Tomás y Miguel Mañara.

Historia

Nomenclator

.

Los distintos tramos de la actual

avenida han pasado por distintos nombres a lo largo del tiempo.

Así, el primero de ellos que va

desde la plaza Nueva hasta el comienzo de la catedral (calles Alemanes y García

de Vinuesa), se llamó tradicionalmente, desde el siglo XIII,

"calle de Génova". Pasando a ser en las primeras décadas del siglo XX

"Cánovas del Castillo" (1897-1931). En

tiempos de la Segunda República Española, pasó a llamarse "Libertad"

(1931-1936); y en la época franquista "José Antonio Primo

de Rivera" (1936-1980).

El segundo sector, desde García de

Vinuesa en dirección a la puerta de Jerez, también se ha conocido hasta hace

poco, y a su vez desde el s. XIII, como "calle Gradas", en el tramo

existente frente a la catedral; y después, a su vez, como "calle de la

Lonja" al correspondiente al frente de la Casa Lonja. En la primera mitad del s. XIX se

concoció tal sector como "Punta del Diamante", y posteriormente

"Catedral" (1868-1877),

"Gran Capitán" (1877-1917),

"Reina Mercedes" (1917-1931), "Libertad" (1931-1936) y

"Queipo de Llano" (1936-1980).

La Avenida actual nace en el primer

tercio del siglo XX, como fruto de una larga serie de actuaciones urbanísticas

en los años previos a la Exposición Iberoamericana de

1929. En este año se inauguró una amplia, larga y recta avenida, aunque estaba

dividida en dos tramos con nombres diferentes:

English

The avenue of the Constitution of

Seville is a wide urban street of modern and straight route that joins, along

600 meters, the Door of Jerez with the building of the City council in the New square.

Located in

the Casco Antiguo district, it delimits the neighborhoods of El Arenal, to the

West - from Plaza Nueva to Adolfo Rodríguez Jurado Street, to Santa Cruz

Street, to the South and East; belonging to the Arenal the even numbers up to

36 inclusive, the rest being part of Santa Cruz. In addition, it marks the

southern limit of the Alfalfa district, in which the town hall building is

inscribed.

It starts at

its northern end, closer to the Town Hall, at the confluence of the plazas

Nueva and San Francisco with Fernández and González street (del Arenal). Next

to it, the streets of García de Vinuesa, Federico Sánchez Bedoya, passage of

the Seises and Almirantazgo, of the Arenal neighborhood converge, and the

streets of Adolfo Rodríguez Jurado and Maese Rodrigo streets of Santa Cruz

neighborhood.

While on the

side of the odd do, to the door of Jerez, the streets Felipe Pérez, Alemanes,

Fray Ceferino González, Santo Tomás and Miguel Mañara.

History Nomenclator . The different sections of the current avenue have gone by different names over time. Thus, the first one that goes from the Plaza Nueva to the beginning of the cathedral (Alemanes and García de Vinuesa streets), was traditionally called, since the 13th century, "calle de Génova". Becoming in the first decades of the twentieth century "Cánovas del Castillo" (1897-1931). At the time of the Second Spanish Republic, it was renamed "Libertad" (1931-1936); and in the Franco era "José Antonio Primo de Rivera" (1936-1980). The second sector, from García de Vinuesa towards the Jerez gate, has also been known until recently, and in turn from the s. XIII, as "calle Gradas", in the existing stretch in front of the cathedral; and then, in turn, as "calle de la Lonja" to the corresponding one in front of Casa Lonja. In the first half of the s. XIX was known as "Punta del Diamante", and later "Catedral" (1868-1877), "Gran Capitán" (1877-1917), "Reina Mercedes" (1917-1931), "Libertad" (1931-1936) ) and "Queipo de Llano" (1936-1980). The current Avenue was born in the first third of the twentieth century, as the result of a long .

of urban actions in the years prior to the

Ibero-American Exposition of 1929. In this year a broad, long and straight

avenue was inaugurated, although it was divided into two sections with

different names:

·

El primero entre la Plaza Nueva y la esquina de Alemanes: primeramente se

llamó “Cánovas del Castillo”, heredando el nombre anterior (desde 1897).

Durante la Segunda República (1931-1936] se unificó con el otro tramo,

recibiendo el nombre conjunto de Avenida de la Libertad. Desde 1936, y hasta

1980, fue la “Avenida de José Antonio Primo de Rivera”.

·

El segundo tramo, desde el anterior hasta la Puerta de Jerez; en su

inauguración fue “Reina Mercedes”. Durante la República se unió al primer

tramo, como “Avenida de la Libertad”. Tras la Guerra recibió el nombre de

“Avenida de Queipo de Llano”, hasta 1980.

En 1980, y con la llegada de la democracia, se cambió

a su nombre actual al conjunto unido en una sola Avenida, que es dedicada a la

Constitución española de 1978.

Antecedentes

Extramuros de

la Hispalis romana, discurría por ella en su

primer tramo un brazo del río Guadalquivir que,

procedente de Alameda, Campana y

plaza Nueva, confluía con el curso principal en el Arenal.

Llegaba hasta la altura de García de Vinuesa —no en

balde antes llamada calle de la Mar—, lo que se conocía como antigua calle

Génova, siendo la entrada fluvial a la ciudad; así se ha encontrado un barco

vikingo en las excavaciones realizadas en la cercana plaza Nueva, donde se

formaba un lagunazo, de las incursiones bárbaras río arriba.

Posteriormente se convertiría en cementerio dicho

sector, de plaza Nueva hasta el edificio de la Punta del diamante, prueba de

ello son las 80 tumbas con restos humanos encontradas en la zona. Debido a los

ataques de los nórdicos normandos sufridos en el siglo IX por la Isbiliya musulmana, que saquean e

incendian la ciudad en 844 y 859, se acometerá la fortificación de la zona,

ampliándose la muralla de modo que la parte de Génova y el sector de la calle

Gradas, segmento hasta la calle Almirantazgo, donde se construye la nueva Mezquita Mayor, quedarán

intramuros por obra de los almorávides.

Habrá una puerta, de ubicación exacta no localizada al

principio de la calle (cerca del ayuntamiento actual, que en el siglo XVI era la antigua lonja), llamada

puerta de los Alfareros, y otra abierta a la altura de Almirantazgo, la puerta

de San Miguel, que en principio era en recodo y después se rectifica para pasar

a ser de bastante amplitud, pues permitiía el paso de dos carros, al final de

la vía (de Gradas).

El último segmento, desde San Miguel hasta la puerta

de Jerez, aún extramuros, era accesible desde dicha puerta y desde la puerta de

la Plata (más conocido en el presente como arquillo de Mañara) del Alcázar de

la Bendición (Alcázar Al Mubarak). Estaba edificado con palacetes y era una

zona de paseo por la pradera de la Plata (Mary al Fidda) y el Tagarete, donde

según parece conocío Al-Mutamid a su esposa Itimad.

Una posterior ampliación de la muralla, efectuada por

los almorávides, acabaría englobando en el perímetro amurallado la totalidad de

la avenida en la primera mitad del siglo XII. A pesar de ello, seguía siendo el

acceso natural de la ciudad al río; así persiste la lonja de pescadería en la

plaza de San Francisco, aunque ya algo lejos del puerto.

El tramo de la mezquita, calle Gradas, era más ancho, y en

él se encontraba la Pila del Hierro, una fuente así llamada por lo cruento de

la batalla en ese lugar durante la toma de 1248; subsistirá la fuente hasta 1618, cuando desaparece con la

construcción de la iglesia del Sagrario de la Catedral.

Con la Reconquista y la llegada de los cristianos se

procede a una reforma de la zona, entre las que están la reconversión de la

mezquita en catedral y la progresiva transformación del último tramo a partir

de la puerta de San Miguel de la muralla en la que progresivamente los

edificios, palacetes, previos se sustituyen por otros, eso sí, manteniendo el

entramado de callejuelas en el área.

English

• The first between the Plaza Nueva and the corner of Alemanes: first it

was called "Cánovas del Castillo", inheriting the previous name

(since 1897). During the Second Republic (1931-1936) it was unified with the

other section, receiving the joint name of Avenida de la Libertad.From 1936,

until 1980, it was the "Avenida de José Antonio Primo de Rivera".

•

The second section, from the previous one to the Puerta de Jerez; at its

inauguration it was "Reina Mercedes". During the Republic it was

united to the first section, like "Avenue of the Freedom". After the

War it received the name of "Avenue of Queipo de Llano", until 1980.

In

1980, and with the arrival of democracy, it was changed to its current name to

be united in a single avenue, which is dedicated to the Spanish Constitution of

1978.

Background Outside the walls of the Roman

Hispalis, an arm of the Guadalquivir river ran through it on its first section,

which, coming from Alameda, Campana and Plaza Nueva, merged with the main

course in the Arenal. It reached the height of García de Vinuesa -not in vain

before called Calle de la Mar-, what was known as the old Genoa street, being

the fluvial entrance to the city; thus a Viking ship has been found in the

excavations carried out in the nearby Plaza Nueva, where a lagoon formed, from

the barbarian raids upstream. Later this sector would become a cemetery, from

Plaza Nueva to the Punta del Diamante building, proof of this are the 80 tombs

with human remains found in the area. Due to the attacks of Norse Norse

suffered in the 9th century by the Muslim Isbiliya, who looted and burned the

city in 844 and 859, the fortification of the area was undertaken, the wall

being extended so that the part of Genoa and the sector from Calle Gradas, a

segment up to Admiralty Street, where the new Great Mosque is built, will be

left intramural by the work of the Almoravids.

There will be a door, exact location not located at the beginning of the

street (near the current town hall, which in the sixteenth century was the old

fish market), called the Potters' Gate, and another one open at the height of

Admiralty, the San Miguel, who in principle was around and then rectified to

become quite large, because it allowed the passage of two cars at the end of

the road (de Gradas).

The last

segment, from San Miguel to the door of Jerez, still outside the walls, was

accessible from said door and from the Puerta de la Plata (better known in the

present as Mañara's arch) of the Alcázar de la Bendición (Alcázar Al Mubarak).

It was built with mansions and was a walking area through the meadow of La

Plata (Mary al Fidda) and the Tagarete, where it seems that Al-Mutamid knew his

wife Itimad.

A later

extension of the wall, made by the Almoravids, would end up encompassing the

entire avenue in the walled perimeter in the first half of the 12th century. In

spite of this, it remained the natural access of the city to the river; This is

how the fish market in the Plaza de San Francisco persists, although it is

already far from the port.

The stretch

of the mosque, Gradas Street, was wider, and in it was the Iron Pile, a source

so named because of the bloody battle in that place during the taking of 1248;

the fountain will remain until 1618, when it disappears with the construction

of the church of the Sagrario de la Catedral.

With the Reconquista and the arrival of the Christians, a reform of the area is being carried out, among which are the reconversion of the mosque into a cathedral and the progressive transformation of the last section from the San Miguel gate of the wall in which progressively the buildings, palaces, previous ones are substituted by others, yes, maintaining the network of alleys in the area.

Historia Contemporánea

Tras la desaparición de la muralla

en el XIX, no será hasta el siglo XX, con motivo

de la Exposición Iberoamericana, que se

derriben los edificios existentes para abrir la actual avenida en su tramo

final hasta la puerta de Jerez.

Proceso de creación

La idea de crear una gran avenida ,

al estilo de las grandes ciudades europeas, que uniera el centro administrativo

y comercial de la ciudad con el exterior, tuvo varios proyectos a lo largo del

siglo XIX, aunque ninguno llegó a dar resultado.

Finalmente se inicia la gran obra

por tramos, con un proyecto del entonces arquitecto municipal José Sáenz y López, que data

de 1906.

Esta operación urbanística contó

con no pocos problemas debido a las demoliciones que debieron realizarse para

conseguir la realización de su trazado, así como a los diferentes pleitos interpuestos

a causa de ello por algunos de los principales propietarios de los inmuebles

afectados.

Quizás el más problemático de estas

demoliciones fue una de las últimas en el tiempo de las llevadas a cabo, la del

antiguo Colegio-Universidad de Santa María de Jesús, junto a la Puerta de

Jerez, que aún estaba en pie a principios del siglo XX impidiendo la

continuidad de la nueva avenida prevista en el ensanche. Cuando en 1915 quedó

acabado el proceso, de dicho edificio sólo quedó la actual Capilla de Maese Rodrigo, que por

quedar a un lado se salvó de la demolición.

De la Plaza Nueva a la Catedral

Así, el primer tramo va desde la

plaza Nueva hasta el comienzo de la catedral (esquina con las calles Alemanes y

García de Vinuesa).

Esta calle anteriormente se llamó

desde el siglo XIII,

"calle de Génova" o de los Genoveses. Pues en el repartimiento de la

Ciudad que realizó Fernando III, entregó unas casas en esta calle a los

comerciantes genoveses para establecer una lonja y consulado (parece ser que en

la esquina García de Vinuesa). Aunque los banqueros y mercaderes genoveses

fueron poco a poco desapareciendo, los sustituyeron los comerciantes de libros:

ha sido famosa por sus imprentas, talleres de encuadernación y comercios de

librería. Era una calle muy concurrida, pero estrecha: menos de la mitad de la

actual Avenida.

Entre los años 1907 y 1912 se

ensanchó y rectificó el alineamiento de esta calle, recortando los edificios de

ambas aceras, especialmente del lado derecho. Desapareció entonces una pequeña

manzana de casas en el extremo de la calle Fernández y González, frente al

arquillo del Ayuntamiento.

La Punta del Diamante

Desde finales del s. XVIII se

conoció al cruce entre Génova, Alemanes, y García de Vinuesa como "Punta

del Diamante", corriendo varias razones para este nombre, que ha perdurado

hasta 2005 en la cafetería “Punta del Diamante” que da nombre al edificio

completo. En la esquina del Sagrario estuvo entre los siglos XIV al XVI la

“Fuente de hierro”, así llamada por una cruz metálica que la coronaba. También

se conocía popularmente a este cruce de calles como “matacanónigos”, por los

vientos fríos que en invierno llegaban provenientes directamente del río por la

Calle del Mar.

Frente al Sagrario, la Catedral y

el Archivo de Indias

El segundo sector, desde García de

Vinuesa en dirección a la puerta de Jerez, también se ha conocido hasta hace

poco, y a su vez desde el s. XIII, como "calle Gradas", “Gradas de la

Catedral” o "Gradas bajas", para diferenciarlas de las gradas de la

calle Alemanes. La calle ocupaba todo el frente a la iglesia del Sagrario y la

Catedral. Posteriormente se llamó "Gran Capitán" (aprox. desde 1870),

"Reina Mercedes" (1917-1931), "Libertad" (1931-1936, como

continuación de Génova con el mismo nombre) y "Queipo de Llano"

(1936-1980).

A continuación estuvo la

"calle de la Lonja" corriendo al frente de la Casa Lonja (hoy Archivo de Indias). Pero

entonces iba mucho más pegada a su fachada, y no existían los jardines. En 1895

pasó a denominarse “Cardenal González”, hasta 1927 en que bautizó como “Primo

de Rivera”.

English

Contemporary history

After the

disappearance of the wall in the nineteenth century, it will not be until the

twentieth century, on the occasion of the Ibero-American Exposition, that the

existing buildings are demolished to open the current avenue in its final

stretch to the Jerez gate.

Creation

process

The idea of

creating a grand avenue, in the style of the great European cities, that

linked the administrative and commercial center of the city with the exterior,

had several projects throughout the 19th century, although none of them came to

any end.

Finally the

great work begins by sections, with a project of the then municipal architect

José Sáenz y López, dating from 1906.

This urban

operation had not a few problems due to the demolitions that had to be carried

out to achieve the realization of its layout, as well as the different lawsuits

filed because of this by some of the main owners of the affected properties.

Perhaps the

most problematic of these demolitions was one of the last in the time of the

carried out, that of the old College-University of Santa Maria de Jesus, next

to the Puerta de Jerez, which was still standing at the beginning of the 20th

century preventing the continuity of the new avenue planned in the widening.

When the process was finished in 1915, only the present Chapel of Maese Rodrigo

remained in that building, which was saved from demolition because it was left

aside.

Thus, the

first section goes from the Plaza Nueva to the beginning of the cathedral

(corner with Alemanes and García de Vinuesa streets).

This street

was previously called from the thirteenth century, "street of Genoa"

or the Genoese. For in the repartimiento of the City that Fernando III carried

out, he delivered some houses in this street to the Genoese merchants to

establish a fish market and consulate (it seems that in the corner García de

Vinuesa). Although the bankers and Genoese merchants were gradually

disappearing, the book merchants replaced them: it has been famous for its

printing presses, bookbinding workshops and bookstore shops. It was a busy

street, but narrow: less than half of the current Avenue.

Between the

years 1907 and 1912 the alignment of this street was widened and rectified,

cutting the buildings on both sidewalks, especially on the right side. Then

disappeared a small block of houses at the end of the street Fernandez y

Gonzalez, in front of the arquillo of the City Hall.

The Diamond

Point

Since the end

of the s. XVIII it was known the crossing between Genoa, Germans, and Garcia de

Vinuesa as "Punta del Diamante", running several reasons for this

name, which has lasted until 2005 in the cafeteria "Punta del

Diamante" which gives its name to the entire building. In the corner of

the Sagrario was between the centuries XIV to XVI the "Fuente de

hierro", so called by a metallic cross that crowned it. This crossing of

streets was also popularly known as "matacanónigos", due to the cold

winds that came directly from the river in the winter along Calle del Mar.

In front of the Tabernacle, the Cathedral and the Archivo de Indias The second sector, from García de Vinuesa towards the Jerez gate, has also been known until recently, and in turn from the s. XIII, as "Gradas Street", "Gradas de la Catedral" or "Gradas bajos", to differentiate them from the stands of Alemanes street. The street occupied all the front to the church of the Sagrario and the Cathedral. Later it was called "Great Captain" (approximately since 1870), "Reina Mercedes" (1917-1931), "Libertad" (1931-1936, as a continuation of Genoa with the same name) and "Queipo de Llano" (1936- 1980). Then there was the "street of the Lonja" running in front of the Casa Lonja (today Archivo de Indias). But then it was much closer to its facade, and there were no gardens. In 1895 it was renamed "Cardenal González", until 1927 when it was named "Primo de Rivera".

Del Archivo de Indias a la Puerta

de Jerez

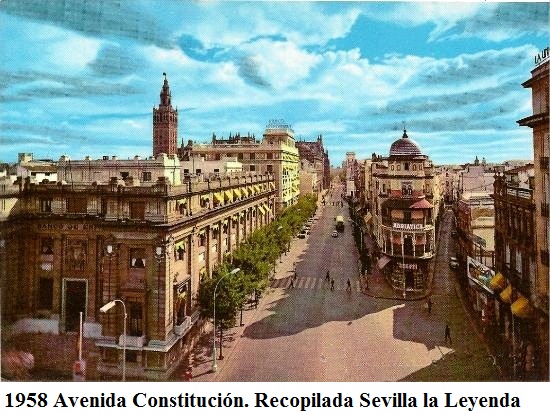

El resto de la actual Avenida, su

tercer tramo, sólo apareció a partir de 1929, tras cinco años de obras previas

a la Exposición Iberoamericana. Antes

había varias manzanas de casas, como se ve en la ilustración.

Tras la calle de la Lonja se pasaba

a la Plaza de Santo Tomás, donde estaba el convento de dicho nombre, que fue

Colegio Mayor de la Orden de Santo Domingo. A esta plaza daba el arquillo de

Mañara por un lado, y por el otro los accesos a la Casa de la Moneda, a la

Aduana (actualmente está la Delegación de Hacienda) y la entrada a la calle

Maese Rodrigo, cuyo tramo central, algo más ancho, se llamó también “Plaza de

la Universidad”. Esta calle bordeaba el primitivo edificio del antiguo

Colegio-Universidad de Santa María de Jesús, hasta desembocar en la pequeña

calle “Jerez”, en el lugar que dejó la Puerta de Jerez al ser derribada en

1864.

Convento y universidad, junto con

los edificios de sus manzanas, fueron derribados para abrir el último tramo de

la Avenida. Esta operación urbanística contó con no pocos problemas debido a

las demoliciones que debieron realizarse para conseguir la realización de su

trazado, así como a los diferentes pleitos interpuestos a causa de ello por

algunos de los principales propietarios de los inmuebles afectados. Se inició la

obra por la parte de la Universidad, entre 1912 y 1815, y la calle resultante

desde Santo Tomás a la Puerta Jerez se llamó inicialmente Reina Mercedes. De la

Universidad sólo perdura la actual Capilla de Maese Rodrigo, que por

quedar a un lado se salvó de la demolición, y la portada de acceso del conjunto

universitario, que se trasladó al compás del convento de Santa Clara, donde aún

permanece.

.

En el año 2009 concluyen

las obras de una falsa peatonalización de la Avenida, en la que se impide el

acceso de los vehículos a motor, incluidos servicios públicos como taxis y

autobuses, y de coches de caballos, sustituidos por un tranvía. Para el

transporte por la Avenida, además de estar permitido el paso indiscriminado a

los ciclistas entre los viandantes, se ha confiado en un moderno modelo de

tranvía (conocido como metrocentro) que se extiende desde la plaza Nueva hasta

el prado de San Sebastián, pasando por la misma Avenida, la puerta de Jerez, la

calle San Fernando y la plaza Don Juan de Austria para finalizar en los

juzgados. El tranvía se mueve a través de un polémico entramado de catenarias,

un antiestético cableado que se ha de retirar cada año con motivo de la Semana Santa del tramo de la carrera

oficial (de la plaza de San Francisco a Almirantazgo). Actualmente se espera

que finalicen las obras de ampliación del metrocentro, desde el prado de San

Sebastián hasta el campus de Ramón y Cajal de la Universidad de Sevilla,

discurriendo así por la Avenida de Carlos V, la calle Enramadilla y la misma

Ramón y Cajal.

English

From

the Archivo de Indias to the Puerta de Jerez The rest of the current Avenue,

its third section, only appeared after 1929, after five years of works prior to

the Ibero-American Exposition. Before there were several blocks of houses, as

seen in the illustration. After the street of the Lonja was passed to the Plaza

de Santo Tomas, where was the convent of that name, which was the College of

the Order of Santo Domingo. To this square it gave the Mañara arch on the one

hand, and on the other the access to the Casa de la Moneda, to the Customs

(currently the Treasury Delegation) and the entrance to Maese Rodrigo street,

whose central section, something wider, it was also called "Plaza de la

Universidad". This street bordered the primitive building of the old

College-University of Santa María de Jesús, until ending at the small street

"Jerez", in the place that left the Puerta de Jerez when it was

demolished in 1864.

Convent and university, along with the buildings of their blocks, were

demolished to open the last section of the Avenue. This urban operation had not

a few problems due to the demolitions that had to be carried out to achieve the

realization of its layout, as well as the different lawsuits filed because of

this by some of the main owners of the affected properties. The work was started

by the University, between 1912 and 1815, and the resulting street from Santo

Tomás to Puerta Jerez was initially called Reina Mercedes. Of the University

only the current Chapel of Maese Rodrigo survives, that for being on one side

was saved from the demolition, and the access cover of the university group,

which was moved to the compass of the convent of Santa Clara, where it still

remains.

.

In 2009 the works of a false

pedestrianization of the avenue, in which the access of motor vehicles,

including public services such as taxis and buses, and horse-drawn carriages,

replaced by a tram, are stopped. In addition to being allowed indiscriminate

passage to cyclists between passers-by, it has relied on a modern tram model

(known as metrocentro) that runs from the Plaza Nueva to the San Sebastián

meadow, passing through along the same Avenue, the Jerez Gate, San Fernando

Street and the Don Juan Square in Austria to finish in the courts. The tram

moves through a controversial network of catenaries, an unsightly wiring that

has to be removed every year on the occasion of Holy Week of the stretch of the

official race (from the Plaza de San Francisco to Admiralty). Currently, it is

expected that the metrocenter expansion works will be completed, from the San

Sebastián meadow to the Ramón y Cajal campus of the University of Seville, thus

running along Carlos V Avenue, Enramadilla street and Ramón y Cajal street.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario